By Xinhua writers Liu Wei, Luo Zhen

BEIJING, Jan. 30 (Xinhua) -- Sun Qiang has loved the story of the Monkey King since childhood. He envies the monkey's duplication magic from which it can create himself from strands of his hair.

Now 45-year-old Sun, director of the non-human-primate research facility affiliated to the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), has become a "magician," who cloned the world's first identical macaques using the method that made Dolly the sheep.

"I can't believe we did it given the hardships we've been through," said Sun, five days after his research was released online by the scientific periodical Cell. "The magic was difficult to practice."

MISSION IMPOSSIBLE

Since Dolly the sheep was cloned from an adult somatic cell in 1997, the cloning of 22 other mammalian species including mouse, cattle, pig, cat and dog has been achieved over the past two decades.

Cloning non-human primates by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) has been a challenge, though.

American Scientists cloned rhesus monkeys using a simpler method called embryo splitting in 1999. That approach is how twins are made, but can only generate up to four offspring at a time, which isn't considered useful for producing large numbers of genetically modified clones for medical research.

Previous attempts to clone monkeys through the Dolly method produced viable embryos but they failed to mature into healthy babies.

"Scientists from the Oregon National Primate Research Center almost succeeded in 2010. The surrogate female monkey had a miscarriage after carrying the embryo for five months," Sun said.

The scientist said it took great courage for his team to accept the assignment of cloning non-human primates.

"The experience from American scientists proved this experiment isn't a mission impossible. But it's always easier said than done," said Muming Poo, a co-author on the study who directs the Institute of Neuroscience of CAS Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology in Shanghai.

UPHILL BATTLE

"We all know sperms have a swimming race to the egg. Only after the sperm activates the egg can an embryo be developed. We often make an analogy: a kiss from the sperm awakens the sleeping beauty," Sun said.

According to Sun, there is no fertilization in cloning, yet the activation is still the key technique for SCNT. The technique starts with removing the DNA-carrying nucleus from an egg cell and replaces it with another nucleus from a differentiated body cell.

"Once an embryo was implanted into the womb of a surrogate mother, we couldn't do much but watch it grow," he said.

However, differentiated monkey cell nuclei, compared to other mammals such as mice or dogs, have proven resistant to SCNT.

Sun's team tried several different methods to overcome this challenge but only one worked. His colleagues and he primarily introduced epigenetic modulators after the nuclear transfer that switch on or off the genes that are inhibiting embryo development. The researchers found their success rate increased by transferring nuclei taken from fetal differentiated cells, such as fibroblasts, a cell type in the connective tissue.

Still, the success rate remained low: just two healthy baby macaques born from more than 60 surrogate mothers. Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua are clones of the same macaque fetal fibroblasts at the end of 2017. Cells from adult donor cells were also used, but those babies only lived for a few hours after birth.

Another challenge lies in procedures. As macaque fetal fibroblasts are not transparent, the enucleation requires precision and speed. The first author Liu Zhen, a postdoctoral fellow, spent three years practicing and optimizing the enucleation procedure.

Liu is able to remove a nucleus within 10 seconds and other team members can complete the injection within 15 seconds.

"The SCNT procedure is rather delicate, so the faster you do it, the less damage to the egg you have," Sun said.

Sun is proud of his team. When starting the experiment, his team had to rent the facility in a suburb of Suzhou, west of Shanghai and 17 members took turns cooking and taking 24-hour shifts to look after more than 1,000 monkeys in case a surrogate female gave premature birth or had a miscarriage.

Speaking of sacrifices his team members made, Sun shed tears.

"We don't have much time to see our family. Fortunately, our efforts paid off," he said

ETHICAL CONCERNS

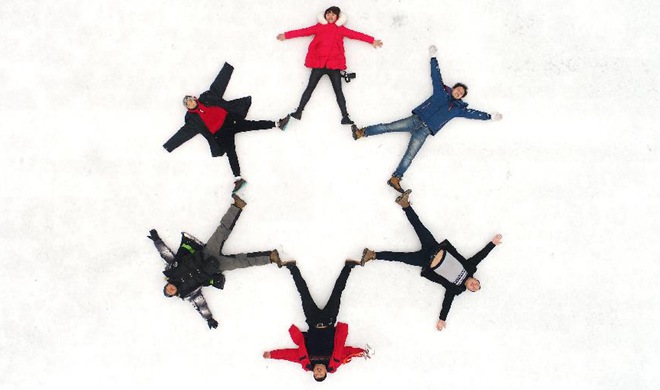

The two cloned long-tailed macaques are currently bottle-fed at the non-human-primate research facility and are growing normally.

"Since these models with identical genes are living in the same environment, researchers will be able to see whether their brains develop in similar ways or naturally diverge. These findings could shed light on many human gene-related diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease," Poo said.

While many researchers are applauding non-human primates as ideal animal for studying physiological functions unique to primates and for developing therapeutic treatments of human diseases, some animal welfare activists in China and abroad have been critical.

Poo said the importance of cloning macaques with the same genes was to reduce the number of farmed animals for experiments.

"Researchers used to use more animals for drug test for accuracy, but now we could change the situation with cloning technology," he said.

Given the red tape, regulatory hurdles and bioethical opposition, scientists from the west are seeking chances in China to collaborate with laboratories for their primate research.

Poo said collaboration was conducive for research, and China would be a hub for pharmaceutical research centers to test new treatments for diseases on non-human primates.

"Any new technology has its silver lining. Gene editing was seen as a monster when first released, but now it is under supervision and applied to many fields. We are working to set strict ethical standards and make sure future research and applications will be monitored under these codes," Sun said.